Latin American Research Centre

we expand horizons

Manuel Álvarez Bravo is one of the most revolutionary Latin American photographers of the 20th century (b. Mexico City, 1902 – d. Mexico City, 2002). Throughout a remarkable 80-year career, his photography evolved to fuse Mexican cultural symbols into a new photographic language, creating icons that have become archetypes of Mexican culture. Bravo’s photos are also recognized as a unique photopoetry, where silence and light portray the human dimension. Contemporaries such as Octavio Paz, Xavier Villaurrutia, Diego Rivera, and especially, André Breton, who went on to lead the Surrealist movement, have all praised Bravo’s witty and incisive eye, a testament of his ability to transform an insightful and ironic view into a universal one. Breton considered Mexico to be the preeminent Surrealist country, and was instrumental in promoting Bravo’s photographs in France, commissioning him to design the catalog cover of the International Exhibition of Surrealism, and publishing his photographs in the French Surrealist magazine Minotaure. In order to better understand Bravo’s Surrealist perspective of Mexico and a reflection of his photography as tangible and eternal evidence of Bretonian Surrealism, the Surrealist tone in Bravo’s photographs as grasped by Breton is explored and explained in this article. While Bravo’s contributions to the modern language of Mexican art are well known, defining him is more controversial. Guillermo Sheridan refuses labeling Álvarez Bravo’s photographic instinct to allow different and unique meanings to the photographs. John Banville perceives the strength of Álvarez Bravo’s multiple artistic approaches. Don Manuel was that kind of photographer for whom reality presented itself as a wide-open range of multiple artistic gazes. Nonetheless, Surrealism was that artistic movement that allowed Álvarez Bravo to play with forms and metaphors.

During Breton’s first visit to Mexico, in 1938, he was especially struck by the convergence of 20th century modernity and pre-Columbian cultures, the pagan cult of Death, and the Mexican proletarian class struggle. Breton was fascinated by the concept of “the marvelous” and its presence in everyday public places such as squares, streets, or parks. He was convinced that magic was present in even the most unexpected or banal everyday object, occurrence, or custom. Similarly, Bravo’s photography focused on the marvelous and the fantastic in everyday life, inadvertently depicting Surrealist concepts in his photographs. Although he did not think of himself as one, he was, from Breton’s point of view, an unexpected Surrealist. In Álvarez Bravo’s photography, the invisible appears magically and unexpected through images such as Dos Pares de Pies, Colchones, or Parábola óptica. Photographs of quirky shapes or word-image games encountered in everyday street life allow us to revisit Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s photography and read his photographs according to Surrealist premises to find many similarities that allow us to rethink the influence Surrealism had on him.

The first instance suggesting Bravo’s work as Surrealistic can be found through the representation of landscapes. Bravo surpassed Hugo Brehme’s influence (on his photography), as well as Guillermo Kahlo’s and Heliodoro J. Guitierrez’s pictorialist urban and rural landscapes, by capturing only parts of objects to depict their whole in his photographs. For example, when looking at Bravo’s photograph “Magueyes heridos” (1950) (“Wounded agaves”), we observe the photo of two agaves, the one on the left cut through its upper leaves and the one on the right cut through its right side. The agave on the left has a leaf cut in the forefront; the agave on the right has a few broken branches on the right side. The title and the synecdochic image connote a damaged millenarian plant commonly grown in Mexico. In Bravo’s photo, however, Mexican Nature is suffering. This is also the case in “Y por las noches gemía” (1945) (“At night it moaned”), a photograph of an old tree trunk with few remaining leaves. The photo is taken from a distance and a point of view (almost 45 degrees left from its forefront) that ultimately creates a sensation of phantasmagoria. The trunk of this old tree now becomes its phantom, as its figure seems to gain a human quality through its location as well as the distance from the photographer.

“Quetzalcoatl" (1970) represents a similar fragmentary approach. The image of a bizarre-shaped tree branch reminds the viewer of Quetzalcoatl’s snake-like tail, which often characterizes the Aztec god as a representation of human unfolding, duality, physical body, and the spirituality in Mesoamerican civilization. Bravo has personified Nature by choosing a specific photographic angle: the tree seems to be a phantom, a gloomy and disconsolate soul; the branches of the tree a living representation of Quetzalcoatl’s tail in movement, just as the agaves seem amputated and disabled without “arms.” A title for each photograph that imparts meaning for the viewer is achieved with this inclination for juxtapositions; for example, “Quetzalcoatl," the name of the pre-Columbian god, connects the photograph – the tree – to a legendary time. In “Y por las noches gemía,” language creates the perception of a downcast and haunted tree (gemir – grieve; noche – night). Surrealist artists were not unaware of this naming technique. Dalí portrays Mae West’s face by playing with furniture, distance, and language through the title of the piece – Mae West's Face (1934-1935), which may be used as a surrealist apartment . By applying this method, Bravo combines an image of Nature and a word or words, and hence, creates a metaphor. Words and images then create a dialectic that weaken but also nurture each other, despite being opposite actions. It is imperative to create a specific meaning since words without images – and it might be said images without words – open an endless possibility of meanings. In addition to this effect, Bravo accomplishes through photography what the French Surrealist writer, Antonin Artaud, observed and described, in 1936, in Mexico, in his book Voyage to the Land of Tarahumaras. By observing the Mexican landscape, Artaud concluded that there was a supernatural aura. For Artaud, objects and subjects among the Tarahumaras are the whimsical result of metaphysical and celestial forces. However, phantasmagorical symbols avoided in Artaud’s text find their way into Bravo’s photographs; that is – in his photographs, the viewer can see a ghost, a god, the suffering of Nature and thereby, a reflection of Nature’s own condition.

Breton’s fascination with pre-Columbian cultures, objects, and people is reflected in representations of indigenousness found in Bravo’s work, the second instance where Surrealism can be found in his photographs. Surrealists showed an active interest in pre-Colonial cultures as a reaction to the political situation in Europe during the inter-war period. In its special second issue, the Surrealist journal Minotaure explored the indigenous African world. For example, Marcel Griaule's photographs in this issue are informative artifacts describing symbols of African ancestral rituals. The historical context of the publication of these photographs and the fact that they were published in Minotaure established these photographs as surreal; it was the time and the context when they were published that made the photographs surreal, not the subjects depicted nor their technique. What Bravo shares with Surrealists is an approach to the ancestral, pre-Columbian and primitive aspects in art, to the detriment of the bourgeoisie. In Surrealist literature and thought, the bourgeoisie are the focus of critics for its individualism, consumerism, and support of capitalism. Bravo translates a hidden reality into an artistic reality when he portrays the integrity of the indigenous people, their clothes, and the totality of their bodies. Bravo captured the everyday lives of Mexico’s indigenous peoples and portrayed their solemnity. For example, in “Baudelia” (1934), “Señorita Juaré” (“Miss Juaré”) (1934), “Tehuana” (1934), “Mujer con dos cabezas de perro” (1930) (“Woman with two dog heads”), “La tierra misma” (1930) (“The land itself”), or “Señor de Papantla” (1934-35) (“Man of Papantla”), subjects are portrayed with majestic dignity. Their solemnity bestows them the right to own the land they have been denied since the beginning of Spanish colonization of Mexico in the 16th century. In “La tierra misma,” a woman partially clothed in a dark muslin cloth is standing up against a wall. Harmony in the photograph is achieved through the subject's blank stare, directed toward the center of the photo, her gaze averting the camera. In this capture, Bravo has achieved a Cartier-Bressonian decisive moment by seizing the subject’s frozen lifeless gaze in a blurry image that is comparable to Surrealist automatism, the flow of irrationality interrupting the cognitive and rational creative process. The title identifies the female body with the land, signifying that the land not represented in the photograph implies its heightened presence to her eyes. In Spanish, land is a feminine word and is related to the female body through linguistic gender. This connection between the female figure and the land can also be seen in “Baudelia” (1934), “Señorita Juaré” (1934), “Tehuana” (1934), and “Mujer con dos cabezas de perro” (1930). In these photographs, these women are portrayed in an absent-but-open landscape. The sun strikes their faces directly and the depicted women are imparted with timeless integrity in the play between light and posture. Bravo’s photographs represent a lethargic time where indigenous people become Mexico, the land itself; the photographer has added a restrained voice of the Otherness to the Mexican melting pot.

Many Surrealist artists also identified landscape and Nature with the female body; Nadja (1928) and Mad Love (1937), by Breton, along with some of his poems, are good examples of such characterization. This may also be observed within the genre of painting, as is the case of Surrealist artist Óscar Domínguez’s “Piano” (1933), where we find the female body and a tree fused together. However, Bravo transcends the Surrealist composition by removing a referential element, the land, and replacing it with the word in the title. His subtle photographic technique is still framed within a Surrealist theme, but he goes further by compelling an iconic analogy between the female body and the land.

In the image “Señor de Papantla” (1934-35), Bravo portrays the figure of a furrow-browed, preoccupied indigenous Mexican. He is standing against a wall, his posture rigid, and he is avoiding eye contact with the camera. The photographic chiaroscuro cast by a tree covers his solemnity and creates an aura of introspection. The title, “Señor of Papantla,” identifies the indigenous man rendered in the image with the northern Veracruz city of Papantla. “Señor de Papantla” obliges the viewer to recollect Octavio Paz’s 1949 Surrealist text, The Blue Bouquet. In this tale, Paz reflects on his identity, living in a village in the Mexican countryside, where he meets an indigenous man described metonymically as small and fragile, wearing a palm sombrero that covers half of his face, fitted with huaraches (Mexican sandals), and holding a country machete. Thus, the sentiment of disenfranchisement is signified in these representations of the people and the land. This split is again built into the metaphor from which Bravo removes the referential dimension, replacing it with the words in the titles, and subsequently creating the very evocative photopoetry of his work.

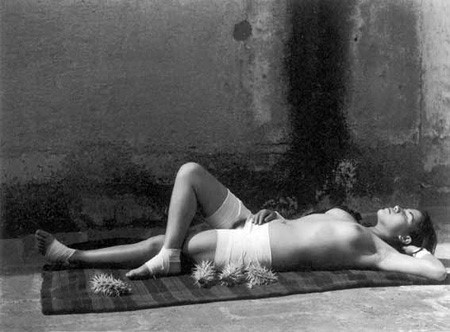

Lastly, the subject of dreaming is the best example of Bravo’s overlapping with Surrealism. His famous photograph, “La buena fama durmiendo” (1938) (“The Good Reputation, Sleeping”), has been considered an eponymous example of Bravo’s Surrealism, both in the way it was taken and in the subject matter connoted in the photograph. Bravo received a call from a man, on behalf of André Breton, asking him for a catalog cover photograph for an exhibition in Mexico. The story is widely known: Bravo, waiting to collect his paycheck from the Academy of San Carlos –where he was teaching photography – saw his former nude class model, Alicia, and asked her to go to the rooftop for a photo. In the meantime, he phoned his doctor, Francisco Marin, to come quickly in order to bandage the model. Bravo asked a security guard to buy “abrojos,” star cacti, that in Spanish means “abre – ojos,” eye(s) wide open. The photograph depicts the model while sleeping – her eyes closed – and unaware of the danger and proximity of these sharp, threatening star cacti that might open her eyes painfully. Puns of this sort are standard Surrealist practice, especially in the writings of Robert Desnos and André Breton. However, what made this photograph surreal was the photographer’s spontaneous decision to have the model posed and immediately photographed. By doing so, Álvarez Bravo created one of the most reproduced photographs of his career. Originally commissioned by Breton for the publication of the Surrealist exhibition catalog, it was censored for its nudity. The photo is not only representative of the Surrealist method, but to an important Surrealist premise: dreams, a topic also explored in Bravo’s other photos, “El soñador” (1931) (“The dreamer”), “María Asúnsolo” (late 1930s), and “El ensueño” (1931) (“Daydreaming”).

In the formal composition of “La buena fama durmiendo” and “El soñador,” the subjects, two indigenous people, are sleeping facing up and lying on the street. The pavement is supporting their bodies and the gray scale of the walls conveys the impression of a wrinkled and blurry background. The linearity caused by the horizontality of the pavement (that supports the bodies) and the verticality of the lines in the walls holds and frames the subjects and creates depth in the photograph. Alicia, the model, and “El soñador” are sound asleep in an unconcerned way and seem unaware of the potential danger (represented by the thorns in “La buena fama durmiendo”) as well as the vulnerability of the act of sleeping. In “El ensueño” and “María Asúnsolo,” the subjects are photographed differently: daydreaming. Both women have their eyes open and their gaze lost in their thoughts, looking inside the photographic frame. The depth of field has changed; María Asúnsolo is inserted in a dark surrounding, and in “El ensueño,” the young girl seems imprisoned by the bars of the stairs. The unusual feeling created by these compositional structures evokes two opposing ways of dreaming: when dreaming carelessly and outdoors, the subjects seem relaxed and sustained by the floor; when daydreaming indoors, the subjects seem preoccupied, lost in their thoughts, and almost swollen by the photographic composition, due to the depth of field.

In 1924, in his first Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton aimed to harmonize dreams and reality into one simultaneous state. Despite being aware of the mystery embedded in the act of dreaming, Breton believed firmly in conquering the unachievable amalgamation of dreams and wakefulness. For the French poet, dreams have a linear and continuous structure that cannot be remembered faithfully in the waking state. Nonetheless, this conquest, which Breton wanted to achieve, seems immortalized in Bravo’s photographs. The viewer, in a conscious state, is observing someone who is sleeping, in his or her dreams. There is a dialog between these two states; image and spectator are needed to complete the meaning of what we are seeing. The viewer is being asked to become a key agent in the construction of the metaphor and when this happens, the visual game and the metaphor become ironic; we all sleep and dream and this is clearly pointed out to the spectators. While looking at the photographs, the spectator may ask him/herself what these people are dreaming about, and through his or her imagination, infinite answers are possible, further creating unique meaning. While not being declared a Surrealist himself, Bravo’s photography depicts Surrealist premises found within Mexican landscapes, indigenous people, or people sleeping. For André Breton, "He has shown us everything that is poetic in Mexico. Where Manuel Álvarez Bravo has stopped to photograph a light, a sign, a silence, it is not only where Mexico’s heart beats, but also where the artist has been able to feel, with a unique vision, the totally objective value of his emotion." And, in doing so, Manuel Álvarez Bravo unintentionally became the unexpected Surrealist.

The views and opinions expressed in this