Latin American Research Centre

we expand horizons

When travelers visit a foreign tourist destination, the money they spend often does not remain in the local economy but rather ends up in a foreign tax haven. Contrary to what many people believe, tourism is not a benign or helpful industry. Through complicated vertically-integrated multinational complexes, large portions of your package price are shaved off into related companies strategically located in low- or no-tax jurisdictions. While emerging economies of Latin America obsess over the large informal sector and tax evasion, multinational corporate tax evasion is as much of a challenge, if not more, than that of the informal sector. The loss of important tax revenues has serious social and environmental consequences for Caribbean and Latin American countries that look to tourism to raise them out of poverty and provide employment. International tourism engenders inequalities with grave consequences. International corporations lure governments into subsidizing expensive infrastructure with the promise of creating instant employment for thousands of workers. But the truth lies elsewhere, perhaps in a tax haven.

The three top Latin American petroleum producers where tourism is an important economic activity are Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela. These three countries account for 68% of the capital flight and 63% of earnings on unrecorded offshore assets. When the fourth country, Argentina, is included, the total increases to 87% of the capital flight and 86% of earnings on unrecorded offshore assets in the region (Ambrosie, 2015; Henry, 2012). Of these four countries, Mexico has the lowest tax effort at 20% of GDP, which is the sum of tax (12%) and petroleum revenues (8%). More than one-third of Mexico’s federal revenue comes from oil. Other OECD members such as Canada collect more than 30% of GDP from tax, and many European countries more than 40% (OECD, 2009).

The example of Cancún and the state of Quintana Roo in Mexico shows that tourism’s benefits began to wane just two decades ago. Starting in 1972, Cancún was developed as a tourist destination with locally-owned hotels of approximately 200-300 rooms each. Only in the 1980s did Cancún attract international investors offering European Plan hotels (i.e. room only). With the exception of lodging and airfare, tourists paid all other services locally. They spent money in local restaurants, purchased souvenirs, and booked local tours. All this was a boon to the local economy and people. Although not impossible, it was hard for local hotel owners to evade taxes because the income paid within the country needed to be declared.

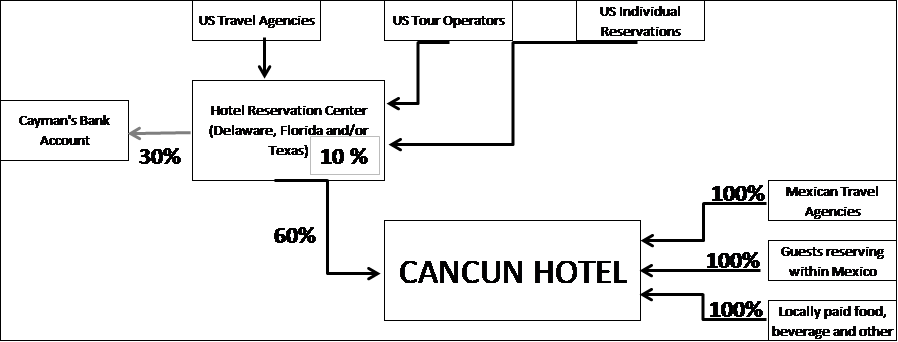

Avoidance in the 20th century (Source: Ambrosie, p.comm)

The original builders of Cancún could not have envisioned the change in the market from European Plan to All-Inclusive Resorts, which were first introduced in France in the 1950s. By including all the services (lodging, food and transportation) in one price, vacationers could budget for travel without surprise expenses at the end of the holiday. Until the 1990s, All-Inclusives remained rare and the small proportion this market represented was mostly dominated by the French chain Club Méditerranée. The turbulent 1980s and early 1990s showed the All-Inclusive business model to be more resilient than European Plan hotels during economic downturns. In addition, many corporations took advantage of the attractive fiscal vehicle called Real-Estate Investment Trusts, or REITs, (in Spanish Fideicomiso de Inversión y Bienes Raíces or FIBRAs), which allowed gains and losses on real estate, such as hotel properties, to flow through to the beneficiaries that hold some or all of the trust. Today, much hotel real estate is owned through this flow-through vehicle.

The now popular and powerful All-Inclusive Resorts are able to avoid corporate taxes through chains of international companies far more complex and complete than ever before, making judicious use of offshore REITs. In addition to the room price, the total package invoiced now includes door-to-destination services, including ground transportation, lodging, food, beverages, recreation and even gratuity.

Avoidance in the 21st century (Reproduced from WB, 2010, p. 115)

The destination-located hotel invoices the international reservation company, perhaps residing in a low- or no-tax jurisdiction, less than the full value of the tourists’ package. The hotel shows a loss at the destination and therefore pays no taxes. When a hospitality multinational wants to build more lodging at a particular destination, such as the Dominican Republic or Mexico for example, the multinational offers local governments the untaxed profits held outside the destination as fresh foreign direct investment (FDI). In exchange for the investment the investors receive tax breaks, subsidies, and publicly funded infrastructure. Perversely, the host country spends federal revenue earned from captured tax-payers, often small businesses and individuals, to attract these foreign investors rather than financing the social projects (such as in health and education) that the captured tax contributors urgently require.

If anyone doubts this scenario, the proof lays in colossal tax loss carry-forwards that the multinational hospitality companies have amassed. By 2012, some of the largest tourism companies had tax-loss carry-forwards amounting to billions of euros.

BCE = Barceló, T.Cook = Thomas Cook (Source: Ambrosie, 2015, p. 99)

Meanwhile, Jamaica and Caribbean Mexico (Cancún and Quintana Roo), which together receive one-third of all land-based tourists to the Caribbean, are both bankrupt and even owe these corporations for declared tax losses. For example, Barceló has at least thirteen properties in Mexico owned and operated through a web of seven Mexican companies interwoven into ninety or more companies worldwide. The corporation boasts over 70% All-Inclusive resort occupancy, yet declared tax loss carry-forwards in Mexico of €3.3 (USD$4) million (BCE, 2012, p. 68)

It is impossible to attribute specific social outcomes to this tax evasion. However, it is through taxes that governments ensure the well-being of their communities through public health services, quality education, and resilient infrastructure. Despite flourishing tourism in Quintana Roo (Mexico), one-third of the population lives in poverty and 7% in extreme poverty. In 2015, the state had the highest rates in Mexico for suicide and teenage pregnancy. These indicators speak to the lack of social programmes financed through tax collection.

The 120 km corridor from Cancún to Tulum (Mexico) supports 70,000 rooms, now almost exclusively All-Inclusives of which more than one-third is owned by Spanish groups. Of the many dozens of major resorts, only five resort owners live in the Cancún area. This heavily impacts not only taxes but also environmental protection. In 2016, major resorts in the area were asked to help finance reef protection for the Meso-American Reef System, which is the second largest reef after the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. Rather than long-term sustainability, distant hotel owners were concerned mainly with profits and as a result, the hotels refused to support the iniative, claiming that they were already paying large amounts of taxes (personal communication).

The claim of tax contributions is true and false simultaneously. Taxes fall into two general categories: direct and indirect. Corporate and personal income taxes are direct taxes because taxpayers remit them directly to the authorities. Indirect taxes such as VAT are collected on taxpayers’ behalf for remittance to authorities. In Mexico, income taxes plus VAT supply 90% or more of the federal government's non-petroleum tax revenue. One study estimated that the Mexican Caribbean federal tax revenue is only 80% of its potential, the fifth poorest tax effort in Mexico (Hernández Trillo, 2011). This suggests that large corporations with their complex webs of companies and transfer pricing are avoiding direct taxes and paying even lower indirect taxes by declaring lower wages that attract payroll taxes and claiming lower than real room rates that attract lodging tax.

The only solution for destinations at the mercy of large hospitality multinationals is indirect taxes such as lodging taxes, VAT and airport taxes collected locally even if the tax base is artificially low. This obvious solution has been ignored because of the claim that indirect tax places a larger burden on low-income earners than high-income earners. While true in some cases, this argument, when applied to international tourism, ignores that resources are consumed mostly by those living outside the tax jurisdiction responsible for resource maintenance. Destinations must seek to impose indirect taxes to ensure that the monies needed to fund environmental protection and social development remain in that locality. Local governments must resist the pressure to subsidize laundered foreign direct investment for mass tourism or risk that the rising tide rather than floating the boat sinks it.

Ambrosie, L. M. (2015). Sun & Sea Tourism: Fantasy and Finance of the All-Inclusive Industry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://doi.org/978-1-4438-7804-3

BCE. (2012). Memoria Anual 2011 (Annual Report 2011). Barceló Corporación Empresarial SA. Retrieved from http://www.barcelo.com/BarceloGroup/es_ES/informacion-corporativa/cifras...

Henry, J. (2012). The Price of Offshore Revisited. Appendix II - Explaining Capital Flight. (T. J. Network, Ed.). Tax Justice Network. Retrieved from http://www.taxjustice.net

Hernández Trillo, F. (2011). ¿Son viables financieramente todas las entidades federativas en México? In Instituto Mexicano de la Competitividad (Ed.), La Caja Negra de las Finanzas Públicas (pp. 54–56). Mexico DF: Instituto Mexicano de la Competitividad.

OECD. (2009). OECD Review of Budgeting in Mexico. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 2009(1), 158.

WB. (2010). Kenya’s Tourism: Polishing the Jewel. Finance and Private Sector Development Africa Region. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org

The views and opinions expressed in this

article are those of the author/s and do not

necessarily reflect those of the LARC..