Latin American Research Centre

we expand horizons

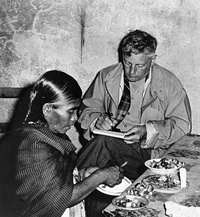

| The dancing hippos, rainbow flowers, and magic mushrooms of Disney’s Fantasia have often been considered indicative of drug-induced experience, reducing young minds to ‘psychedelic rubble’ according to one review. And little wonder, since Disney was inspired not only by surrealist artist Salvador Dali (Figure 1) but also by visions from Mazatec shaman and healer Maria Sabina in the mountains of southern Mexico. Maria Sabina is noted for introducing hallucinogenic mushrooms to such drug gurus as Timothy Leary, John Lennon, and Mick Jagger (Figure 2). In this article, we consider how art is transformed by extra-sensory experience, and how that experience can be recognized even long ago, in the pre-Columbian past. Specifically, we discuss shamanic visions encoded in the visual culture of the ancient Americas using a case study from Late Postclassic (1300-1525 CE) Pacific Nicaragua. |  |

|

|

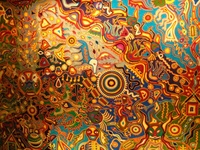

Contemporary attempts to illustrate hallucinogen-induced visions or trance in art can be found in different cultures. For example, the modern-day Huichol of northwestern Mexico incorporate their peyote-induced visions in their art, where a central theme is often the peyote cactus integrated with creatures with supernatural significance, especially deer and serpents (Figure 3) (Schaeffer 1996, 2002). The multi-colour weavings, as well as yarn art and beadwork, present a complex montage of images meaningful to artists as they attempt to re-capture and record their visions. In Central America, the mola art of the Kuna in Panama also uses brightly coloured yarns to illustrate mythological scenes and visions inspired during shamanic trances. The theme of Kuna shamanism from San Blas island specifically references carved wooden figurines used in curing and divinatory rituals (Fortis 2013). |

|

|

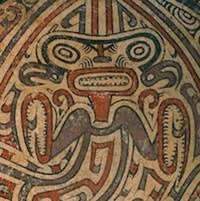

But to what extent were similar themes illustrated in ancient art? Pottery decorated with cosmological imagery was found on 3000 vessels from Paquime/Casas Grandes in northern Mexico from about 1300 CE (VanPool and VanPool 2007). Images of birds, humans, and serpents were predominant in their iconography (Figure 4), while more common animals abundant in the faunal assemblage were nearly absent. Anthropologists Christine VanPool and Todd VanPool concluded that the ceramic symbolism in the pottery related to a fundamental shamanic world-view. Shamans acted as intermediaries between the natural and supernatural. The animals selected for pottery decoration are precisely those able to cross between planes of a three-tiered cosmos: birds of the heavens and earth, and serpents of the earth and underworld. |

|

|

VanPool and VanPool suggested in 2007 that there were different stages of a vision: during the first stage one sees geometric designs such as zigzags, grids, dots, and parallel lines that are subsequently interpreted as shapes, snakes, birds, fish, or other animals. In Stage 2 the shaman experiences a vortex of shapes swirling and undulating around him or her. By the next stage the shaman is in a complete trance, transforming into their animal co-essence (e.g., jaguar, bird, or other creatures). They are typically flying, often accompanied by a spirit guide to navigate this otherworldly dimension, which is described as a chaotic sensory overload. Elaborate iconography is also a trait in pottery from Central America, where it is again interpreted as directly related to shamanism (Labbé 1995). Animal-like images ranging from naturalistic to fantastic are abundant motifs, and are often embedded in panels of radiating lines (Figure 5). Here again, these are likely the recordings of trance-like visions. A common trait of visions experienced by shamans of Central as well as South America is the ability to transform into animal co-essences to travel in the natural realm and communicate with the supernatural (Stone 2011). Jaguars, as one of the most powerful and ferocious creatures, were prominent spirit animals, but many other creatures were also used. Other zoomorphic images combined aspects of multiple animals to create fantastic creatures. |

|

|

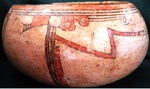

Archaeological, ethnohistoric, and historical linguistic data all provide information on the pre-Columbian cultures of Pacific Nicaragua (Abel-Vidor 1981; Chapman 1974), and this can be supplemented by interpretations of the rich visual culture preserved on decorated ceramics, stone sculpture, and other elements of material culture. A hint at ancient belief systems is found on polychrome pottery, where painted and incised iconography of both realistic and ‘fantastic’ creatures provide some indication of the natural world and its potential relationship with the supernatural (Lothrop 1926). During the Postclassic Sapoá/Ometepe periods of Pacific Nicaragua (800-1525 CE), polychrome decoration was very common on ceramic serving wares, with many different motifs Ethnohistorical sources describe a pantheon of deities derived from the central Mexican Nahua culture, including a rain god (Quiateot), and wind god (Hecat), among others (León Portilla 1972). Archaeological evidence to support this Mexicanized religion focuses on polychrome ceramics depicting the Feathered Serpent (Figure 6), an avatar of Quetzalcoatl/ Ehecatl (Lothrop 1926; Manion and McCafferty 2017). While the Colonial sources derive almost exclusively from Nicarao informants, ‘feathered serpent’ iconography in fact first appears several centuries before the supposed arrival of the Nahua Nicarao and is more likely an introduction of the Oto-Manguean Chorotega, another group that originated in southern Mexico (McCafferty 2015). |

|

|

Another prominent polychrome motif from Pacific Nicaragua is found on Luna Polychrome, a type of ceramic characterized by fine line painted motifs on a cream coloured slip, dating to the Late Postclassic/Ometepe period of 1300-1525 CE (Knowlton 1996). The predominant image on Luna Polychrome represents a stylized praying mantis (McCafferty and McCafferty 2019). The largest group of Luna vessels were superhemispherical bowls with painted decoration on the exterior (and occasionally the interior) (Figure 7). These often included an image of a creature with long, multi-jointed front legs, a segmented body, triangular to ovoid head, and lines suggesting antennae. A long tongue protrudes from the head, and a circular object is characteristically depicted behind the head. These attributes can all be related to the praying mantis (although a mantis lacks a tongue, the incredible speed with which it captures prey is interpreted in traditional lore as a tongue, like a frog or lizard)). |

|

|

In Nicaraguan oral tradition, the praying mantis is recognized as a prodigious hunter able to capture, kill, and consume much larger prey, for example birds and lizards (Prete and Wolfe 1992). The females are infamous for decapitating and consuming their mates during copulation. Mantids are also regarded as having divinatory powers, such as being able to predict the weather or lead a traveler home when lost. The praying mantis is referred to as the ‘mother serpent’ (madre culebra) in Nicaragua. This bears a strong resemblance to one of the prominent Nahua deities, Cihuacoatl, or ‘woman serpent.’ Cihuacoatl was associated with death and rebirth, and especially with spiritual communication (Klein 1988). The goddess and her priestesses are often depicted with a skeletal mandible, reminiscent of the multi-faceted jaws of the praying mantis. Interestingly, priestesses associated with the goddess are depicted in the Codex Borbonicus (1979) holding hallucinogenic mushrooms during rituals (Figure 8). We suggest that depictions of mantids on Luna Polychrome correspond to an animistic relationship with a local avatar of Cihuacoatl, and that in elaborate examples the mantis imagery is presented as a visual depiction of a shamanic vision. These are especially associated with Luna ‘face bowls,’ in which a human face emerges from the exterior surface of hemispherical bowls while mantis iconography wraps around the rest of the exterior surface (Figure 9). As the madre culebra, mantids may have incorporated animistic concepts from Chorotega and autochthonous Chibchan communities with innovative religious concepts from newly arrived Nahua people. In this way, the mantis became integrated with the Nahua Cihuacoatl and the result was depicted on the Ometepe-period diagnostic Luna Polychrome. |

|

| Within the native religion of Pacific Nicaragua, however, no pantheon of deities can be identified prior to the arrival of Mexican migrants. Instead, the archaeological evidence points toward an animistic religion of environmental and animal spirits, with ritual practitioners (or shamans) acting as intermediaries between the natural and supernatural realms (Day and Tillet 1996; Klein et al. 2002). The best evidence for this practice is found in the ubiquitous ceramic figurines representing seated or standing females, usually with their hands on their hips or thighs (Wingfield 2009; Figure 10). This general posture remained consistent throughout the cultural sequence from at least 500 BCE; with the introduction of polychrome decorative technology beginning in the Postclassic/Sapoá period (ca. 800 CE) the female figurines also included painted decoration on mold-made heads and bodies. In particular, the oversized heads featured exaggerated oval eyes and painted decoration around the mouth, in a style identical to the ‘face bowls’ associated with mantis imagery on Luna Polychrome. We interpret these as possible visual referents to the ‘mother serpent,’ as personified mantids. As female shamans merged with their animal co-essences they may have been able to access the spirit realm for the purpose of divination. |  |

|

The use of hallucinogens would have amplified the connection, similar to the use of trance-inducing substances known from ethnographic examples elsewhere in Central America and in northern Mexico (Reichel Domatoff 1975; Schaeffer 1996). And just as among pre-Columbian groups from Panama to northern Mexico (at least), these visions may have been recorded onto the material culture, in this case on decorated pottery. The pervasive use of mantis imagery may have referred to the spirit guides who accompanied the shaman on vision quests, or who carried the souls of the deceased to the land of the dead. In conclusion, one of the predominant motifs on Ometepe period pottery has strong affiliation with the praying mantis as the madre culebra and may be related to a local avatar of the Nahua goddess Cihuacoatl. This connection may finally provide archaeological support for the ethnohistorically-documented migration and colonization of Pacific Nicaragua by the Nahua Nicarao people. As native and migrant ideologies merged during the Postclassic period, the animism of shamanic practice may have been memorialized on Luna Polychrome vessels that depicted a transformation into supernatural praying mantis beings. The mantis, as a voracious female predator, would have been a symbolic embodiment of the goddess and a strong spirit guide while traversing supernatural realms. |

|

References

1981 Ethnohistorical Approaches to the Archaeology of Greater Nicoya. In Between Continents/Between Seas: Precolumbian Art of Costa Rica, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 85-92. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, New York.

Chapman, Anne C.

1974 Los Nicarao y los Chorotega segun los fuentes historicas. Ciudad Universitaria, Costa Rica.

Codex Borbonicus

1979 Códice Borbónico: Manuscrito Mexicano de la Biblioteca del Palais Bourbon. Siglo Veintiuno, Mexico DF, Mexico.

1994 Central Mexican Imagery in Greater Nicoya. In Mixteca-Puebla: Discoveries and Research in Mesoamerican Art and Archaeology, edited by H.B. Nicholson and E. Quinones Keber, pp. 235-248. Labyrinthos Press, Culver City, CA.

Day, Jane Stevenson and Alice Chiles Tillett

1996 The Nicoya Shaman. In Paths to Central American Prehistory, edited by Frederick W. Lange, pp. 221-236. University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO.

2013 Kuna Art and Shamanism: An Ethnographic Approach. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

1988 Re-Thinking Cihuacoatl: Aztec Political Imagery of the Conquered Woman. In Smoke and Mist: Mesoamerican Studies in Memory of Thelma D. Sullivan, edited by J.K. Josserand and K. Dakin, pp. 237-277. BAR International Series, Oxford, UK.

Klein, Cecelia F., Eulogio Guzman, Elisa C. Mandell, and Maya Stanfield-Mazzi

2002 The Role of Shamanism in Mesoamerican Art: A Reassessment. Current Anthropology 43:383-419.

Knowlton, Norma E.

1996 Luna Polychrome. In Paths to Central American Prehistory, edited by Frederick W. Lange, pp. 143-176. University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO.

1995 Guardians of the Life Stream: Shamans, Art, and Power in Prehispaninc Central Panama. Bowers Museum of Cultural Art, University of Washington Press.

1972 Religión de los Nicaraos: Análisis y Comparación de Tradiciones Culturales Nahuas. Instituto de Investigaciones Historicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico, DF.

1926 The Pottery of Costa Rica and Nicaragua, 2 vols. Heye Foundation, Museum of the American Indian Memoir 8, New York, NY.

Manion, Jessica and Geoffrey G. McCafferty

2017 Serpientes Emplumadas del Pacifico de Nicaragua. In Arqueología de Nicaragua: Memorias de Mi Museo y Vos, edited by Nora Zambrana Lacayo, pp. 302-308. Mi Museo, Museo del Arte y Arqueología Precolombina, Granada, Nicaragua.

2008 Domestic Practice in Postclassic Santa Isabel, Nicaragua. Latin American Antiquity 19(1): 64-82.

2015 The Mexican Legacy in Nicaragua, or Problems when Data Behave Badly. In Constructing Legacies of Mesoamerica: Archaeological Practice and the Politics of Heritage in and Beyond Mexico, edited by David S. Anderson, Dylan C. Clark, and J. Heath Anderson, pp. 110-118. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, Volume 25.

McCafferty, Geoffrey, and Carrie L. Dennett

2013 Ethnogenesis and Hybridity in Proto-Historic Period Nicaragua. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 28 (1): 189-212.

2017 El horizonte cerámico de engobe blanco del Postclásico Temprano de México y Centro América. In Arqueología de Nicaragua: Memorias de Mi Museo y Vos, edited by Nora Zambrana Lacayo, pp. 316-329. Mi Museo, Museo del Arte y Arqueología Precolombina, Granada, Nicaragua.

McCafferty, Geoffrey and Sharisse McCafferty

2019 Symbols of Insect Animism on Luna Polychrome. Mi Museo y Vos. Granada, Nicaragua.

McCafferty, Geoffrey G. and Larry Steinbrenner

2005 The Meaning of the Mixteca-Puebla Style: A Perspective from Nicaragua. In Art for Archaeology’s Sake: Material Culture and Style across the Disciplines, edited by Andrea Waters-Rist, Christine Cluney, Calla McNamee and Larry Steinbrenner; pp. 282-292. Proceedings of the 2000 Chacmool Conference, Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary, Calgary, AB.

1992 Religious supplicant, seductive cannibal, or reflex machine? In search of the praying mantis. Journal of the History of Biology, 25(1), 91–136.

Reichel-Dolmatoff, G.

1975 The shaman and the jaguar: a study of narcotic drugs among the Indians of Colombia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

1996 The Crossing of the Souls: Peyote, Perception, and Meaning among the Huichols. In People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, and Survival, edited by Stacy B. Schaefer and Peter T. Furst, pp. 138-168. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM.

2002 To Think with a Good Heart: Wixarika Women, Weavers, and Shamans. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

2011 The Jaguar Within: Shamanic Trance in Ancient Central and South American Art. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

VanPool, Christine S. and Todd L. VanPool

2007 Signs of the Casas Grandes Shamans. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Wingfield, Laura M.

2009 Envisioning Greater Nicoya: Ceramics Figural Art of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. c. 800 BCE - 1522 CE. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Departmet of Art History, Emory University. Atlanta, GA.