Latin American Research Centre

we expand horizons

Photos: Brett Nelson and Mary Catherine Driese

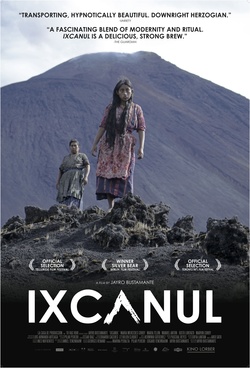

On July 14, 2016, Oxlajuj Aj, a non-governmental organization studying Kaqchikel (Maya) language and culture, was invited to attend a screening of Ixcanul [sic], the first feature-length motion picture featuring Kaqchikel actors and purporting to represent Kaqchikel culture. The film is spoken almost entirely in Kaqchikel, and the viewer is invited to believe that it shows a Kaqchikel reality and to assume that the problems shown are particular to the Kaqchikel. This is disingenuous, to say the least.

Because the film is spoken

|

Oxlajuj Aj is a non-governmental organization, sponsored by Tulane University, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Texas, with fellowship support from the U.S. government through the Foreign Language Area Studies program. Over the past thirty-one years, more than three hundred people have studied Kaqchikel (Maya) language and culture with this organization. During this same period, eighty native-speaker scholars have worked with Oxlajuj Aj as consultants, lecturers, language instructors, and spiritual and cultural guides. Oxlajuj Aj has contributed to the development of educational resources used and distributed by the Guatemalan Ministry of Education, both for teacher training and for use directly in schools with K-12 students learning Kaqchikel, the Indigenous language mandated for all students in the Departments (Guatemalan equivalent to Provinces or States) of Sacatepéquez, Chimaltenango, and Sololá.

On July 14, 2016, Oxlajuj Aj was invited to attend a screening of Ixcanul [sic] at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala (UVG). As this is the first feature-length motion picture featuring Kaqchikel actors speaking Kaqchikel and purporting to represent Kaqchikel culture, it was important that Oxlajuj Aj attended, especially as there was to be a panel discussion with one of the producers, one of the economic backers, and a UVG professor. The movie is beautifully filmed, edited, and produced. The story it tells is heart and gut-wrenching. It has won international acclaim and has been awarded prizes at multiple film festivals. Over a year and a half later, the film continues to be screened at various functions, including at a March 8, 2018 celebration of International Women’s Day by the University of Calgary’s Latin American Research Centre (LARC) at the Calgary Public Library.

On July 14, 2016, Oxlajuj Aj was invited to attend a screening of Ixcanul [sic] at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala (UVG). As this is the first feature-length motion picture featuring Kaqchikel actors speaking Kaqchikel and purporting to represent Kaqchikel culture, it was important that Oxlajuj Aj attended, especially as there was to be a panel discussion with one of the producers, one of the economic backers, and a UVG professor. The movie is beautifully filmed, edited, and produced. The story it tells is heart and gut-wrenching. It has won international acclaim and has been awarded prizes at multiple film festivals. Over a year and a half later, the film continues to be screened at various functions, including at a March 8, 2018 celebration of International Women’s Day by the University of Calgary’s Latin American Research Centre (LARC) at the Calgary Public Library.

The film purports to present real-life issues in an only mildly fictionalized form. Because the film is spoken almost entirely in Kaqchikel, the viewer is invited to believe that it shows a Kaqchikel reality and to assume that the problems shown are particular to the Kaqchikel. The Kaqchikel members of Oxlajuj Aj challenged these assumptions during the discussion period following the UVG screening. But their protests were deflected by the producer and financial backer. Whenever a Kaqchikel complained that their culture was misrepresented, or that an event shown would not be contemplated within their worldview, the producer responded “es una ficción” (it is fiction). However, it should be noted that María Mercedes Coroy, the actor who portrayed the main character, told Licenciada Ixnal Cuma Chávez, an Oxlajuj Aj instructor, in a personal interview (August 2016) that she was representing the real-life tragedy of a woman from Sololá, whom Mercedes had interviewed to gain perspective on her role. In interviews, director Jayro Bustamante also affirmed the idea that the film is based on a true story (September 2015, and December 2015).

At the UVG screening, the financial backer claimed that the problems shown, particularly “child marriage” and “drunkenness,” are real. While the members of Oxlajuj Aj, Kaqchikel, non-Maya Guatemalans, and international students and scholars agreed that some child marriage still occurs and that drunkenness can be an issue, they maintained that these concerns are not specific to the Kaqchikel, nor to the Maya population, but are generalized problems in Guatemala as a whole. Deeply affected by the screening, Oxlajuj Aj continued to deliberate on the issues and elected to release a statement presenting a nuanced Mayan opinion on the representation of their culture. This essay presents the main points raised in two days of careful discussion.

First, Oxlajuj Aj praised the director, Jayro Bustamante, for presenting a film in fluent Kaqchikel. Unlike other recent movies in Indigenous languages, this film does not script the dialogue and then give the major speaking roles to non-native actors. These actors speak in their own language with elegant fluency. Oxlajuj Aj also acknowledged the expert camera work, highlighting the panoramic vistas of the volcanic slopes of Pacaya.

Having acknowledged these positive aspects of the film, Oxlajuj Aj listed the social ills that the film depicts: general lack of education; lack of employment opportunities, fueling emigration to the North; exploitation of workers through company stores, a modified form of debt peonage; arranged marriages (though not all believe this practice to be ill-considered); teen pregnancy, which is linked to lack of sex education; machismo (though there is little of this actually shown in the film, which focuses on two strong women); theft of infants; extreme poverty; and lack of public services (health care, legal assistance, education) in Indigenous languages.

In 2014, 60% of the Guatemalan people

|

Of these ills, only the latter is an exclusively Indigenous problem. Non-Mayan Guatemalans (colloquially known as Ladinos) experience all other difficulties as well. In 2014, for example, 60% of the Guatemalan people were living below the poverty line, and if one looks exclusively at the Indigenous populations, the situation is even direr, with 80% of the population living in poverty (World Bank 2014). The World Bank estimates that 6% of the population emigrates looking for work (2011). While President Jorge Ubico (1931 to 1944) outlawed debt peonage in the 1940s (McCreery 1983), the modern agricultural labor minimum wage of $3 per day is seldom met. UNICEF notes that 26% of school-age children do not attend school and that annual drop-out rates hover at 12% (n.d.).

Child theft in Guatemala has mythic standing. Guatemalan Attorney General (Procurador General de la Nación) Vladimir Aguilar, in a 2014 interview published in Prensa Libre, reported that in 2013 five children had been abducted, and a like number for 2014. A 2013 dissertation submitted to the Virginia Commonwealth University presents the cases of three children abducted in Guatemala in 2006 (Monico 2013). One abduction was from a Mayan family; the other two from non-Maya homes. Though the Alba-Keneth Alert System was introduced in August of 2010, anxiety over child theft remains high (Siu 2012). The U.S. Department of State 2015 report on crime in Guatemala notes: “Particularly in small villages, residents are often wary and suspicious of outsiders. Guatemalan citizens have been lynched for suspicion of child abduction.” The 2017 and 2018 U.S. Department of State reports reiterate warnings to its citizens in Guatemala: “The Embassy recommends that U.S. citizens refrain from actions that could fuel suspicions of child abductions.”

The rituals are depicted as ineffectual

|

As Ixcanul [sic] was being filmed, the Guatemalan Congress was acting to limit the very kind of child marriage shown in the film, passing Decreto 8-2015. This law set the legal marriage age at eighteen, with the proviso that a judge could allow marriage at age sixteen if it was determined to be in the best interest of the bride. The law was strengthened in 2017 (Decreto 13-2017) to set the bar, unequivocally, at age eighteen.

This film illustrates and denounces basic ills in Guatemalan society. It does so through the lens of a vignette set in a Kaqchikel community, purposely abstracted from a real setting, unbeknownst to many viewers. The actors are all from the town of Santa María de Jesús and speak the distinctive variant of Kaqchikel spoken only in this community and not in any other Kaqchikel town. They are dressed in attire emblematic of Sololá, a Kaqchikel town far from Santa María de Jesús. Both language and dress are important indicators of identity within Kaqchikel culture, however, the fictive plantation on which they work is on the slopes of the volcano Pacaya, a non-Kaqchikel region. Thus decontextualized, the story could be that of plantation life, but it is essentialized as Kaqchikel, with the Kaqchikel standing as an avatar for Indigenous people.

This film illustrates and denounces basic ills in Guatemalan society. It does so through the lens of a vignette set in a Kaqchikel community, purposely abstracted from a real setting, unbeknownst to many viewers. The actors are all from the town of Santa María de Jesús and speak the distinctive variant of Kaqchikel spoken only in this community and not in any other Kaqchikel town. They are dressed in attire emblematic of Sololá, a Kaqchikel town far from Santa María de Jesús. Both language and dress are important indicators of identity within Kaqchikel culture, however, the fictive plantation on which they work is on the slopes of the volcano Pacaya, a non-Kaqchikel region. Thus decontextualized, the story could be that of plantation life, but it is essentialized as Kaqchikel, with the Kaqchikel standing as an avatar for Indigenous people.

Several elements in the movie contradict the basic values, practices, and ascriptions of Kaqchikel communities. The Kaqchikel scholars of Oxlajuj Aj found the dismissal and transgression of Kaqchikel religio-philosophical norms offensive. Kaqchikel ideology holds that all elements of the universe are sentient beings. As such, the scene in which María is in the forest sexually aroused amidst nature can be viewed as a form of abuse of the tree, which is both shocking and offensive.

Even more offensive was the manner in which Mayan spirituality was portrayed. The rituals are depicted as ineffectual and eventually irrelevant, and thus, their practitioners and communicants as superstitious and ignorant. Particularly poignant scenes involved ceremonies in front of the syncretized Ma Ximón figure. The characters’ repeated pleas are never answered. Rilaj Mam is also shown to be a false idol.

Perhaps most disturbing is one of the central artistic tropes of the film. We are introduced to the female leads as they bring a boar to service a sow. Once the boar has been presented to the sow, María leans over the fence to watch and observes, man nirajo’ ta “he doesn’t want to.” Her mother then produces two bottles of clear rum. She feeds one to the boar and María pours the contents of the second bottle down the throat of the sow. This liquid aphrodisiac works. Later in the film, when María wishes to instigate a sexual relation with her boyfriend, she brings a bottle of rum to stimulate their liaison. Another scene briefly shows María and her mother walking down a mountain road carrying firewood bundles on their heads. They come upon an agonizing pregnant cow, lying in the road dying. They comment that the cow has been bitten by a viper. Later, María, pregnant with her lover’s child, goes into a field to drive out the snakes infesting it and is bitten by a serpent. Throughout the film the Kaqchikel, and by extension Guatemalan Mayan peoples, are likened to animals.

Perhaps most disturbing is one of the central artistic tropes of the film. We are introduced to the female leads as they bring a boar to service a sow. Once the boar has been presented to the sow, María leans over the fence to watch and observes, man nirajo’ ta “he doesn’t want to.” Her mother then produces two bottles of clear rum. She feeds one to the boar and María pours the contents of the second bottle down the throat of the sow. This liquid aphrodisiac works. Later in the film, when María wishes to instigate a sexual relation with her boyfriend, she brings a bottle of rum to stimulate their liaison. Another scene briefly shows María and her mother walking down a mountain road carrying firewood bundles on their heads. They come upon an agonizing pregnant cow, lying in the road dying. They comment that the cow has been bitten by a viper. Later, María, pregnant with her lover’s child, goes into a field to drive out the snakes infesting it and is bitten by a serpent. Throughout the film the Kaqchikel, and by extension Guatemalan Mayan peoples, are likened to animals.

Less strikingly, but tellingly, the director and producers of the film, though ostensibly committed to exposing the structural inequities faced by Mayan people in Guatemala, do not bother to learn enough of the language to correctly spell the title of the movie, the only place where the language appears in print. The correct orthography for Kaqchikel was made official by the Congreso de la República in 1987 (Decreto 1046-87). The Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala (ALMG) was established in the same year and legally recognized in 1990 (Decreto 65-90). The standard and official forms of Kaqchikel have been taught at all levels from elementary school through high school since 2003, and the official writing system is taught in all the national schools in the five departments in which it is the official language. The official orthography was almost thirty years old at the time of the release of the film. In this orthography, the word for “volcano” is Ixkanul. Using the Spanish-based spelling Ixcanul underscores the point of view of the film, that of a non-Maya looking at the Maya but not bothering to come to know them.

The director and producers

|

The spoken Kaqchikel is beautifully performed. Though the actors are all fluent in Spanish and, though the common communicative norm in Santa María de Jesús is to sprinkle Spanish and English borrowings throughout conversation, almost no loanwords appear in the dialogue. In part, this is to underscore a central point of the film, that the Maya are constantly disadvantaged by their inability to speak Spanish and the corresponding inability of the non-Maya public service officials and agents to speak the vernaculars of the communities they “serve.” The spoken Kaqchikel is fluent, hyper-correct, and true to the dialect of the actors’ home town. Despite using the Kaqchikel language, this is an outsider’s perspective on Kaqchikel life. It denigrates their spiritual belief system, inviting the ascription of “superstition”; it depicts them as drunkards, showing important social encounters, such as marriage negotiation, as drink-fests; it suggests that ills that beset all poor Guatemalans are Indian problems; and it depicts Indigenous people as bestial.

The movie is beautifully filmed and acted. María Mercedes Coroy is lovely as the eponymous heroine. But Ixcanul [sic] is racism made beautiful.

Bibliography

Further Reading

Berry, N. S. (2013). Unsafe motherhood: Mayan maternal mortality and subjectivity in post-war Guatemala. New York: Berghahn Books.

Carey, D. (2006). Engendering Mayan history: Kaqchikel women as agents and conduits of the past, 1875-1970. New York: Routledge.

Fischer, E. F. & Hendrickson, C. (2018). Tecpán Guatemala: A Modern Maya Town in Global and Local Context. New York: Routledge. (Original work published 2003 by Westview Press)

French, B. M. (2010). Maya ethnolinguistic identity: Violence, cultural rights, and modernity in highland Guatemala. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Green, L (1999). Fear as a Way of Life: Maya widows in rural Guatemala. New York: Columbia University Press.

Little, W. E. (2000). "Home as a place of exhibition and performance: Mayan household transformations in Guatemala." Ethnology 39(2): 163-181.

Otzoy, I. (2008). "Indigenous law and gender dialogues." Human Rights in the Maya Region: 171-186.

The views and opinions expressed in this

article are those of the author/s and do not

necessarily reflect those of the LARC.