Latin American Research Centre

we expand horizons

A number of innovative efforts to protect the environment have taken place in Ecuador over the last decade. Possibly the most significant is the 2007 Yasuní-ITT (Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini) initiative, which proposed to conserve parts of the Amazonian rainforest by banning the extraction of nearly 900 million barrels of oil in the area. In exchange, the aim was for the international community to grant Ecuador conservation funds amounting to half the estimated oil revenue in the Yasuní reserve.

The Yasuní-ITT initiative was presented by former President Rafael Correa at a United Nations assembly in 2007 as a challenge to the international community. The Yasuní region is recognized as one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, containing five times more mammalian species than Banff National Park in Canada. [1] In 1979 UNESCO decreed parts of it a National Park and an Ecological Reserve, and the Yasuní-ITT project aimed to halt oil drilling and instead promote investment into social, environmental, and livelihood-related programs beyond oil extraction. [2] The initiative was in line with reforms to the Ecuadorian Constitution in 2008, which granted legal rights to nature. This novel and radical strategy to pursue post-neoliberal development is grounded in the Quechua ‘buen vivir’ or sumak kawsay (collective well-being) worldview, which refers to a deep-rooted respect for nature and the lifestyles of indigenous groups, a notion that has resonated with similar initiatives in Bolivia and Brazil.

Following six years of unsuccessful campaigning to obtain the stipulated minimum level of international funding and support, in 2013 President Rafael Correa officially declared the Yasuní-ITT initiative failed and approved oil drilling in Yasuní National Park. Today oil extraction in the Yasuní has increased ecological and social tension in the area, as the local population fears that oil drilling may risk potential spills and consequent health risks, along with unstable livelihoods for people dependent on temporary employment. The effects of oil drilling might also encroach on the lands of the Tagaeri and Taromenane indigenous groups, who live in voluntary isolation in an ‘untouchable zone’ that intersects the National Park.

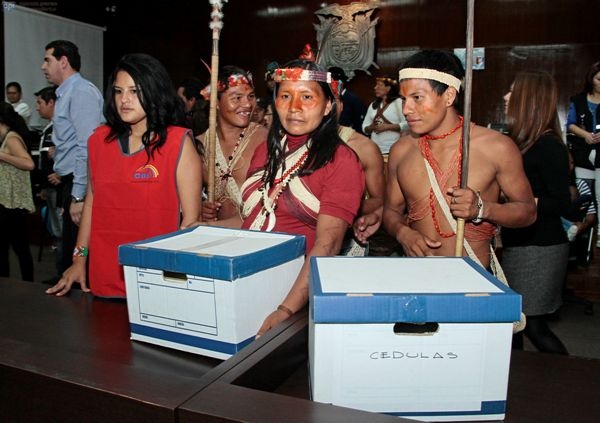

In response to Correa’s decision to approve oil extraction, several groups formed the YAsunidos Collective in August 2013, in an attempt to revitalize the initiative to protect the Yasuní by proposing a popular consultation on the subject. The campaign began collecting signatures in October of that year, but by March 2014, Yasunidos had failed to collect enough signatures to prompt a consultation. Yet following Ecuador’s presidential election in 2017, newly-elected President Lenín Moreno has reopened the discussion about the future of the Yasuní project and recently called for a plebiscite on it, to be undertaken on February 4th of this year.

President Lenín Moreno—the first paraplegic person to be elected president in Latin America—has built a reputation as a strong supporter of social rights and for promoting a different style of public discourse as part of his platform to “dignify politics”. During his presidential campaign, he promised a major campaign against corruption, along with a less hostile government than his predecessor, Rafael Correa, who had been criticized as authoritarian and intolerant.

President Moreno launched a national public dialogue in June 2017. He has invited several social movements, including journalists and opposition politicians, to discuss pressing national issues, such as taxation, public investment, and the environment.

Moreno’s efforts toward a more open national dialogue have boosted his popularity after a narrow election victory last year. The desire to move past a conflictual campaign, where different sides accused each other of fraud, has added momentum to the call for a plebiscite in search of a more open and transparent political process. When Moreno’s administration invited the public to submit questions on key national issues for his suggested plebiscite, they received over 400 proposals.

In early October 2017, Moreno proposed two questions for a referendum and five more for public consultation, including one that directly addresses the conservation of the Yasuní National Park:

“Do you support increasing the protected zone by at least 50,000 hectares and reducing the petroleum exploitation zone that was authorized by the National Assembly in Yasuní National Park from 1,030 hectares to 300 hectares?” (translated by the authors).*

By contrast to former President Correa, Moreno has encouraged Ecuadorians to vote “Sí” on protecting the Yasuní. Correa had endorsed Lenín Moreno as part of their joint political movement ‘Alianza País,’ but has now come to criticize him, arguing that the Yasuní plebiscite strategy is dishonest. In a recent interview, Correa was quoted as saying that “5 out of the 7 questions are trash,” arguing that the Yasuní case could just as well be “a simple executive decision.” Correa argues that his government already knew during the initial Yasuní ITT initiative that oil drilling could be accomplished by only using around 250 hectares (780ha less than the initial plan), and that all the oil could be drilled regardless of the proposed plebiscite.

This raises questions about Moreno’s larger motives and strategy. Why is the Yasuní question reemerging now, and why in the format in which it has been proposed?

The proposed list of seven plebiscite questions suggests a combination of “hard” and “soft” issues that, as a whole, may shed light on the political significance of Moreno’s revived Yasuní initiative.

Three of the proposed plebiscite questions are “hard” questions that go against Correa’s suggested policies: (1) whether to cancel the unlimited re-election of public authorities, which had been approved by a constitutional amendment during Correa’s government; (2) whether to restructure the Council for Citizen Participation and Social Control (the fifth power of the Ecuadorian state), which had been strengthened in the 2008 Constitutional assembly and promoted by Correa; and, (3) whether to cancel a law that taxes real estate gains (“La Ley de Plusvalía”). The conservative opposition to Correa had resisted all of these policies during his administration, and would likely applaud their end.

The other four questions are “soft” and far less contentious. These pertain to: (1) implementation of stricter penalties for sex crimes against children; (2) disqualification of individuals involved in corruption from participating in political life; (3) the general prohibition against mining in urban centers, protected areas, and protected zones; and (4) the direct question on increasing the protected zone and reducing the oil drilling area in the Yasuní, mentioned above.

The list of proposed questions, along with Moreno’s inclusive consultation strategy, suggest that Moreno may want to appease the opposition to Correa’s government and to distance himself from his predecessor’s administration. He has a strong incentive to do so, given his narrow election victory last year.

Moreno’s policy of dialogue has nevertheless been criticized for being overly inclusive. One of the most controversial political figures invited to the dialogue process was Dalo Bucaram, former Member of Parliament, presidential candidate 2017, and son of former President Abdalá Bucaram. The Bucaram family has long been accused of corruption, since Bucaram’s brief presidency between 1996-1997. Former President Correa has described Bucaram’s inclusion in the dialogue as treason to the “Revolución Ciudadana.”

Indeed, Moreno’s approach has led to growing hostilities with former President Correa. In a controversial decree, Moreno directed the country's electoral council (Consejo Nacional Electoral) to approve the proposed plebiscite before the Supreme Court had a chance to rule on its constitutionality. Correa openly criticized the plebiscite and its rushed approval, suggesting Moreno’s approach was unconstitutional. Moreno, on the other hand, argued that the plebiscite was urgent and that legal approval was taking too long.

The wording of the Yasuní plebiscite question has also been criticized as overly vague. The YAsunidos campaign, for example, welcomes the inclusion of the Yasuní in the plebiscite, but argues that “an increase of 50,000 hectares is insufficient for the survival of the Yasuní’s isolated communities.” They also call for more specifics on the precise location of the protected zone. They suggest that the lack of detail could be intentional to protect the government and oil companies from being forced to stick to their commitments in the region. The Tambococha oil field in the Yasuní-ITT is currently in the second phase of active exploration and drilling.

There are many reasons why Moreno might have taken up the initiative to protect the Yasuní. These range from a sincere desire to protect the environment, to a narrower political calculation to distance himself from his predecessor and strengthen his own political base. Regardless of whether it stems from altruism or self-interest, Moreno’s plebiscite could be grounds for cautious optimism for environmental conservation and sustainable livelihoods in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

*The protected zone (in Spanish “zona intangible” —literally, “untouchable zone”) was created in 1999 by a presidential decree that pursued the protection of the area in question from any extractive operations, including oil drilling.

1. Bass, M.S.; Finer, M.; Jenkins, C.N.; Kreft, H.; Cisneros-Heredia, D.F.; McCracken, S.F.; Pitman, N.C.; English, P.H.; Swing, K.; Villa, G. Global conservation significance of Ecuador's Yasuní National Park. PloS one 2010, 5, e8767.

2. Davidsen, C.; Kiff, L. Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT Initiative and New Green Efforts-Away from Petroleum Dependency. Occasional papers 2013, 3.

The views and opinions expressed in this

article are those of the author/s and do not

necessarily reflect those of the LARC.